Thank You for Being Honest: The Films of Ira Sachs at MoMA – –

The Museum of Modern Art presents a complete, mid-career retrospective of the films of Ira Sachs, a filmmaker who, in the course of seven features and five short films, has established himself as one of the singular voices in American cinema.

From July 22 to August 3, Thank You for Being Honest: The Films of Ira Sachs will showcase the complete range of Sachs’s intimate work, from experimental shorts to insightful social comedies to piercing autobiographical dramas, in the Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters. The series begins and ends with films that premiered with Sundance. Forty Shades of Blue (2005), which won the Sundance 2005 U.S. Dramatic Grand Jury Prize, will open the retrospective. The film is the emotionally gripping story of an aging Memphis record producer, hard drinker, and cad (Rip Torn), and his relationships with his Russian girlfriend (Dina Korzun) and his son Michael (Darren Burrows). The July 22 screening will be followed by a Q&A with Sachs, conducted by Rajendra Roy, Celeste Bartos Chief Curator of Film at MoMA. The exhibition is organized by the Department of Film.

Filmmaker Ira Sachs, with seven features and five short films, has established himself as one of the singular voices in American cinema.

The series closes with Sachs’s most recent film, Little Men (2016), starring Greg Kinnear, Jennifer Ehle, and Paulina Garcia, and featuring breakout performances by two extraordinary 12-year-olds, Michael Barbieri and Theo Taplitz. The film explores the lives of two Brooklyn families and how their relationships are impacted when one inherits a brownstone containing a storefront rented by the other. As their sons become fast friends, tensions erupt among the adults over a rent hike, putting the boys’ friendship in peril. The August 3 screening will also include a Q&A with Sachs, conducted by Roy.

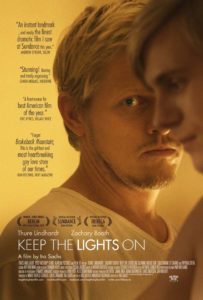

In Sachs’s early films—The Delta (1997), Forty Shades of Blue, and Married Life (2008)—the protagonists find themselves in their own very isolated and painful processes of self-discovery. In these three very different, but closely aligned works, the central relationships are either fueled or destroyed by secrets. Keep the Lights On (2012), Sachs’s most autobiographical film, is a “bridge” between his earlier work and the present since it shows characters hiding important parts of themselves from each other. Inspired by Sachs’s own troubled 10-year relationship with a charismatic—and drug-addicted—male partner, the film is a significant re-certification of Sachs’s position as a leading voice in New Queer Cinema.

In Sachs’s later films, Love Is Strange (2014) and Little Men (2016), there is a new lightness that revels in the comedy of everyday life. For the first time, the central relationships that drive the films have an integrity and honesty that was absent in his previous stories. The much-lauded Love Is Strange, which was nominated for four Independent Spirit Awards in 2014, stars Alfred Molina and John Lithgow as a long-time gay couple whose marriage ironically leads to their separation. In Little Men, it is the intimate bond of two friends that is threatened by the enmity and limitations of the adult world around them.

The series also includes Sachs’s first film, Vaudeville (1992), which follows a traveling theatrical troupe consisting primarily of gay and lesbian performers. The tensions within the tight-knit troupe mirror the troubles of larger political and social communities. In the short Lady (1994), the exact identity of the redhead at the center of the film is impossible to pin down. Is she a woman playing a man playing a woman or, more specifically, a lesbian playing a gay man playing a heterosexual woman? This purposeful ambiguity invites the audience to question the blurred parameters of sexuality, desire, and female identity. In Last Address (2009), Sachs, who first moved to New York City in 1984, uses images of the exteriors of the houses, apartment buildings, and lofts where New York artists (and others) who died of AIDS over the last 30 years were living at the time of their deaths to mark the disappearance of a generation. The elegiac film is both a remembrance of that loss and an evocation of the continued presence of their work in our lives and culture. Sachs arrived in New York in the heart of the AIDS epidemic, and a mood of political anger and sorrow—and a deep understanding of the impact of social forces on the lives of the individual—suffuses his work.

The series also includes Sachs’s first film, Vaudeville (1992), which follows a traveling theatrical troupe consisting primarily of gay and lesbian performers. The tensions within the tight-knit troupe mirror the troubles of larger political and social communities. In the short Lady (1994), the exact identity of the redhead at the center of the film is impossible to pin down. Is she a woman playing a man playing a woman or, more specifically, a lesbian playing a gay man playing a heterosexual woman? This purposeful ambiguity invites the audience to question the blurred parameters of sexuality, desire, and female identity. In Last Address (2009), Sachs, who first moved to New York City in 1984, uses images of the exteriors of the houses, apartment buildings, and lofts where New York artists (and others) who died of AIDS over the last 30 years were living at the time of their deaths to mark the disappearance of a generation. The elegiac film is both a remembrance of that loss and an evocation of the continued presence of their work in our lives and culture. Sachs arrived in New York in the heart of the AIDS epidemic, and a mood of political anger and sorrow—and a deep understanding of the impact of social forces on the lives of the individual—suffuses his work.